Bible prophecy: Who Is "Babylon"?

Who is the “great harlot” and Babylon the Great? The “great prostitute,” as the Greek is sometimes translated, is discussed in several chapters of Revelation under the figure of Babylon (17:1-19:3).

Who is the “great harlot” and Babylon the Great? The “great prostitute,” as the Greek is sometimes translated, is discussed in several chapters of Revelation under the figure of Babylon (17:1-19:3).

To understand how to interpret the identity of the “great harlot” and Babylon, we need to read the entire passage. The account begins in the first four verses of Revelation 17 by introducing us to this “great prostitute.” She is pictured as having committed adultery with the rulers of all nations. The people throughout the world have become awe-struck by her power.

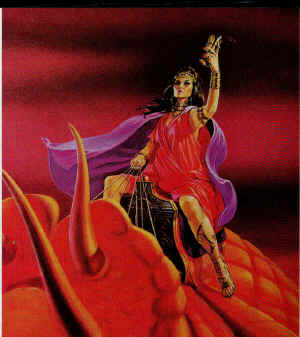

This fallen woman sits on a scarlet or red beast with seven heads and ten horns. She is adorned with extravagant jewelry and holds a golden cup in her hand, the contents of which depict her political and social adultery. This brings us to the end of verse 4. At this point in the text, we do not know who this “great harlot” is. But we already know that the Bible uses the symbol of prostitution and harlotry to depict idolatry and worldliness. That is, sexual perversion is symbolic of anything spiritually evil and against God.

When we read verse 5, we are given a kind of identity of the “great harlot.” It is: “Babylon the Great, the mother of prostitutes and of the abomination of the earth.” So the “great harlot” is Babylon the Great. From verse 5, the harlot is described under the symbol of Babylon, and this continues into the beginning of chapter 19.

Babylon – symbolic name for Rome

This Babylon the Great could be seen in John’s time as Rome or the Roman Empire, as a type. (The Christians who first read Revelation almost certainly understood it in that way.)

Most commentators believe that Revelation uses “Babylon” as a code word that can refer to the Rome of John’s day. “Like Babylon of old,” says Robert H. Mounce, Rome “had gained a worldwide reputation for luxury, corruption, and power” (The Book of Revelation, The New International Commentary on the New Testament, p. 310). Mounce then quotes Tacitus, who describes Rome as the place “where all the horrible and shameful things in the world congregate and find a home” (Tacitus, Annals. xv.44).

The Jewish apocalyptic writings of the time also use Babylon as a symbolic name for Rome. The Sibylline Oracles say that a star “will burn the deep sea and Babylon itself and the land of Italy, because of which many holy faithful Hebrews and a true people perished” (5.159-161). It calls Babylon the “city of the Latin land, unclean in all things” (5.168).

There is a good reason why the connection was made between the Babylonian and Roman Empires. Says Norman Perrin, “Rome is called Babylon because her forces, like those of Babylon at an earlier time, destroyed the temple and Jerusalem” (Jesus and the Language of the Kingdom, p. 58). The Babylonians had destroyed Jerusalem and the temple in the 580s B.C. and sent its people into captivity (2 Kings 25; Jeremiah 52). The Roman Empire did essentially the same thing in A.D. 66-70. Thus, Rome was Babylon all over again.

More than Rome

Babylon the Great, however, stands for a world system more universal than that of the old Roman Empire. In the words of biblical scholar Robert W. Wall, she is: “The ‘global village’ of godless power, which determines daily life for every person at any time in human history” (Revelation, New International Biblical Commentary, p. 202).

“The great city is every city and no city,” said Leon Morris of this Babylon the Great. “It is civilized man, mankind organized apart from God. It has its embodiment in every age” (Revelation, revised edition, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries, p. 203).

What does Babylon the Great represent? It is a symbol that stands for all the ungodly religious-political-social-economic systems that humans have created. As John might put it in his letters, Babylon is simply “the world” (1 John 2:15). The world system depicted under this symbol would be that one that does not reflect God’s nature of love, and which in turn enslaves mankind.

Babylon the Great may have represented the mother goddess of the ancient Near East, Athena, or the goddess Roma, or the power structure of Assyria – to mention three ancient examples. She may be state-sponsored religion or ideology in the service of worship of the state at any time in human history. If we extend the metaphor to its limits, Babylon can also be found wherever men and women use religion, ideology or political-economic power to further their ungodly aims in opposition to the things of God. But these are all just types or precursors.

In Old Testament Scripture the ancient city of Babylon stood for the power structure of evil that opposed God. That image is carried over into the book of Revelation. One commentator summarizes the book as “A Tale of Two Cities.” It is Babylon the Great versus the New Jerusalem. Just as the New Jerusalem personifies the perfection and eternal state of the kingdom of God, Babylon the Great personifies the kingdom of humanity, which is to be destroyed.

Revelation’s image of Babylon the Great is a timeless one. While it can be seen in every civilization – no human empire to date has been the Babylon. Its final emergence must be reserved for the close of history. The picture of Babylon the Great’s destruction is seen to occur at the close of history, when God judges the world in Jesus Christ the returning Word of God on the white horse (19:11-13). See Revelation 18-19 for the full story of the “end of the world” and the return of Jesus Christ.

When we see these great universal themes that attach themselves to the symbol of Babylon the Great, it is clearly unscriptural to equate Babylon with any Christian church, including the Catholic Church. The “Catholic” church did not become an organized body with political power until the early 300s A.D. long after Revelation was written. If Babylon was a reference to the Catholic Church, then the book of Revelation would not have been understood by its first readers.

The message of Revelation was sent to real Christians living around A.D. 100, and they must surely have understood its contents. We also know from the apocalyptic literature of the period that people knew the meaning of the symbols used in the book of Revelation. This would have included the metaphor Babylon the Great, which would have been understood as the Roman Empire.

We could probably apply this metaphor by extension to, for example, the corrupt corporate church of the Middle Ages. It did have some characteristics that are described under the “Babylon the Great” symbol. But there is no biblical evidence to back up the 19th century Protestant claim that vilified the Catholic Church as the harlot of Revelation, chapter 17.

Author: Paul Kroll