Jesus Christ: Where Was Golgotha?

Where did the pivotal event of all the ages take place?

Archaeology sheds new light on an old controversy.

The death and resurrection of Jesus Christ was the most significant event in all history! The precise location where he was crucified, buried and resurrected has intrigued Christians for many centuries. The fact of that great event does not depend on locating the authentic site. But it is only natural that Christians would have an interest in knowing where their Savior died—and where he rose again.

What does the Bible tell us about the location? The Gospel writers call the place where Jesus was crucified Golgotha—an Aramaic word meaning “the skull.” Calvary is the Latin form of the word. Scripture does not reveal the precise location of Golgotha. It simply states that Jesus’ crucifixion took place outside the city of Jerusalem, though near it (John 19:20; Hebrews 13:12). Jewish law did not permit executions and burials inside the city.

Further, we know that Jesus was crucified near a well-traveled road, since passersby mocked him (Matthew 27:39; Mark 15:21, 29-30). The Romans selected conspicuous places by major highways for their public executions. The crucifixion probably took place on a hill, because it was visible at a distance (verse 40). As for the tomb or sepulcher, we’re told only that it was in a garden near the place of crucifixion (John 19:41).

Rival sites of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial

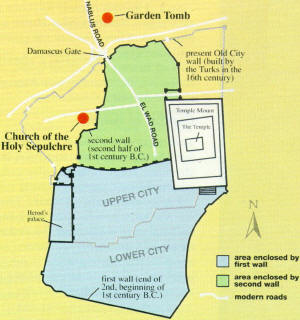

Various locations around Jerusalem have been suggested as the site of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial. But in recent times, only two have been deemed worthy of serious consideration. The traditional site lies within the area now occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (at right), in the Christian Quarter of the Old City (see map below). The huge church embraces within its walls a hill called Latin Calvary, and nearby, the traditional tomb of Christ.

The other contending location is a rocky hill— commonly called Gordon’s Calvary—just north of Jerusalem’s Old City (see map). It was named in honor of a British military leader, General Charles Gordon, who promoted the site in the 19th century. Near Gordon’s Calvary is a quiet garden, with a rock-hewn tomb popularly called the Garden Tomb, held by some to have been the sepulcher of Jesus.

Golgotha outside city walls

In recent decades, archaeological excavations have revealed more facts about the Jerusalem of Jesus’ day—including the route of the city walls at that time. As we have seen, the Bible requires that Golgotha lie outside those walls.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is inside the walls of today’s Jerusalem. Does that disqualify it as the authentic site? No. The walls that now surround the Old City are not the walls of Jesus’ day. They were built in the 16th century. Excavations and literary evidence show that when Jesus was crucified, the line of the city wall ran south of the site on which the Church of the Holy Sepulchre now stands (see map).

Ancient tradition is another important consideration when evaluating alleged holy sites. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre has a longstanding tradition in its favor that can be traced back to the time of Constantine, the first Roman emperor to profess Christianity. According to tradition, Queen Helena, Constantine’s mother, made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in a.d. 326. The Christians living in Jerusalem at that time pointed out the location of Calvary and Jesus’ tomb to Helena and her traveling companion, the historian Eusebius.

It was an unexpected place—they claimed that the holy site lay underneath Jerusalem’s Temple of Venus (or Aphrodite), which had been built by the Roman Emperor Hadrian a century after Jesus’ crucifixion, when pagan temples were built in the city after the Jewish revolt of a.d. 135.

|

|

| Gordon’s Calvary |

The Garden Tomb |

Helena ordered the pagan temple demolished and removed to uncover Jesus’ tomb and Calvary. The excavations revealed several ancient tombs. Evidence pointed to one in particular as the tomb of Christ. The workmen also uncovered a rocky outcrop that was identified as the hill of Calvary. A church was built adjacent to the site in a.d. 335—the forerunner of today’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Can we trust a tradition as late as the fourth century? Though Hadrian banned all Jews from Jerusalem in a.d. 135, Christians not of Jewish ancestry could and did live in Jerusalem from Hadrian’s time on. Eusebius even preserves a list of the Gentile bishops of Jerusalem. A tradition could therefore have easily been passed down through generations of Christians to Constantine’s time.

Consider, too, that Jerusalem’s Christians were so certain the tomb lay under the Venus temple that they persuaded Helena to pay for the demolition of the temple. Had they not been certain that a tomb and rocky hill lay beneath it, they would been less likely to suggest the costly work. Their conviction must have been tied to a long and consistent tradition.

The place of the skull

What of the notion that Golgotha was named because it in some way resembled a skull? The rough shape of a human skull—with eye sockets, nose and mouth—is visible in the cliff face of Gordon’s Calvary (see photo above). Scripture, however, requires no such features.

The notion that Golgotha, “The Place of the Skull” (Matthew 27:33), was named because of the appearance of the hill is a modern idea. From early Christian times, virtually all commentators held that Golgotha was so named simply because it was a place of execution, where the skulls and bones of criminals lay scattered.

Further, Gordon’s Calvary was probably part of a ridge—not a separate hill—in Jesus’ time. The features of the hill that make it look like a skull were not present in the first century. Archaeologists believe it to be a quarry or mine developed only in the past two or three centuries. In other words, its skull-like appearance is the result of modern quarrying operations.

The fact that Gordon’s Calvary was suggested only recently is, in itself, clear testimony that the hill did not resemble a skull until relatively recent times. Otherwise, it would have been suggested as an alternative candidate for Golgotha in earlier centuries. Yet no ancient or

medieval tradition connects the crucifixion with the place.

Garden Tomb is too old

Jesus’ tomb was a “new tomb” (Matthew 27:60). Any tomb not identifiable as a first-century tomb is out of the running. Archaeological work has shown that the ancient rock-cut tombs within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre are indeed first-century tombs, as required by Scripture.

The Garden Tomb, by contrast, was originally hewn out centuries earlier—in the Iron Age, in the eighth or seventh century B.C., during the time of the later kings of Judah. This determination is based on the plan and characteristics of its rooms, the type of chisels used in cutting out the tomb, the artifacts excavated inside, and other factors. Thus, it does not qualify as a “new tomb” of the first century.

Is it important to know?

The verdict of archaeology seems to be clear: Gordon’s Calvary and the Garden Tomb have little evidence in their favor. What of the site now occupied by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre? It seems to have the weightier claim as the actual location of Jesus’ crucifixion and burial. We

cannot know with 100 percent certainty, and it is not important that we know. Salvation does not hinge on a particular location, but on the reality of the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Readers who would like to know more about the archaeological investigations into the Garden Tomb and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre may consult the March/April 1986 and May/June 1986 issues of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Author: Keith W. Stump