Money: Are You Living Beyond Your Means?

I live in a society in which I regularly receive offers for credit cards. The offers tell me I am “pre-approved.” Some offers encourage me to take a second mortgage on my home.

I live in a society in which I regularly receive offers for credit cards. The offers tell me I am “pre-approved.” Some offers encourage me to take a second mortgage on my home.

Other advertisements encourage me to buy various products and services. “Easy credit” is available, I’m told. “Free gift for applying.” “Buy now, pay later.” “Instant approval.” “Take up to three years to pay.”

Whether you live in a credit society or not, let’s take a look at the problems of credit in the United States, where I live. For what is occurring in the U.S. could likely be visited on many nations long range.

Dramatic rise in consumer debt

In 1990, the average American adult owed more than $4,000 in installment credit (not counting house mortgages). Since many people have no debts at all, others owe much more — in some cases, more than they make each year.

Certain kinds of debt may be appropriate. Most people need to borrow money to be able to buy a home. Some need to borrow money to buy a car. But credit is often used to buy consumer goods and luxuries, leaving little to show for it except the bills. Many people try to buy more — and more often — than they need. Banks and businesses encourage it.

The catch is that we still have to pay, and, until we do, we have to pay interest, often as much as 18 percent. Many families lose $1,000 each year in interest payments on installment debts. The result is that these debts reduce their future standard of living.

When expenses exceed income

People may hope that their income will increase enough to pay the bills. This may happen sometimes, but it cannot be counted on. For many, average wages, after adjustment for inflation, have gone down.

U.S. installment debts are growing about 8 percent each year. Payments on mortgage and consumer debts absorb almost three fourths of the average annual income after taxes. For some people, there’s not much left. One credit card is used to pay another; one bill is delayed so an overdue bill can be paid. (For other warning signs of being too far in debt, see the box below.)

Some statistics indicate that Americans cannot afford any more debt. In the United States, personal bankruptcies doubled in the past decade. Most of the people who filed for bankruptcy had jobs. Unexpected bills or reductions in pay caused the bankruptcy.

If bankruptcies increased in the 1980s, when the economy was going well, what will happen when a recession comes, when more people lose jobs? Not all economists agree about when a recession will come, or how severe it will be, but they agree that recessions do come. For example, Alan Greenspan, Federal Reserve Board chairman, warned Congress about the U.S. federal debt: “Allowing deficits to persist…risks potentially significant reductions…in our standard of living.”

Harvard University economist Benjamin Friedman warned: “The reason that the average American has enjoyed such a high standard of living lately is that since January 1981 our government has simply borrowed more than $20,000 on behalf of each family of four… The costs, which are only beginning to come due, will include a lower standard of living for individual Americans” (Day of Reckoning, Benjamin Friedman, pages 4).

Because of the importance of international trade, any U.S. recession will affect other nations. Jobs will be lost. Pension funds can become bankrupt. Corporations can be taken over by new managers. Even government agencies can be made “more efficient,” privatized or simply eliminated. A recession can affect everyone.

Even now, many families live from paycheck to paycheck, with little or no reserves for emergency expenses. A temporary loss of job would be unbearable. Because of the uncertainties of the economy, and even of our own health, it is wise to get out of debt and to save a reserve for emergencies that will come.

Paying off your debts isn’t easy. You’ll need to make some temporary reductions, but the benefits are worth it. What strategies will help you pay off your debts? How can you make a plan to pay all your bills and keep expenses within your income? You’ll find some practical advice on these topics in our series Personal Money Management.

A major benefit of getting out of debt is that you’ll save money by avoiding interest payments. And you’ll be more secure. That’s an economic principle. There is also a moral principle involved.

Violating a “moral principle”

A bumper sticker put it bluntly: “We are spending our children’s inheritance.” Yes, this generation is spending more than it has. Benjamin Friedman comments: “We have enjoyed what appears to be a higher and more stable standard of living by selling our and our children’s economic birthright.” We have “violated the basic moral principle that had bound each generation of Americans to the next … that men and women should work and eat, earn and spend … so that their children and their children’s children would inherit a better world” (Day of Reckoning, page 4).

It is interesting that this respected economist refers to a moral principle. He begins the first chapter of his book with a quote from the Bible: “A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children” (Prov. 13:22).

The Bible has much to say about basic economic principles: “Beware of covetousness, for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of the things he possesses” (Luke 12:15). “Let your conduct be without covetousness, and be content with such things as you have” (Heb. 13:5). See also Proverbs 22:7.

Dr. Friedman says that our generation is failing in moral and economic responsibility. He referred to government debts, but the same is true for many personal debts. Don’t wait for hard times to come before taking action. “Like fish taken in a cruel net, like birds caught in a snare, so the sons of men are snared in an evil time, when it falls suddenly upon them” (Eccl. 9:12).

The time to get out of debt is now!

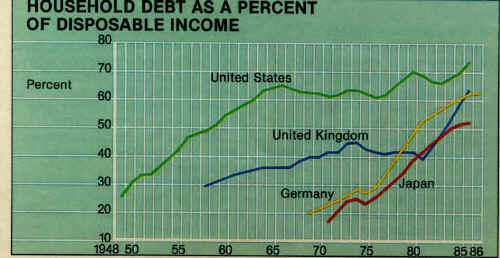

Credit: Comparing Four Nations

United States: Americans tend to borrow more than citizens of other nations do. Why? In the first four decades after World War II, as incomes increased, Americans had an ever larger increase in money available for nonessential consumer goods and to establish credit. As they accumulated more household wealth, they became more credit-worthy, both to lenders and in their own eyes. The result has been the social acceptance of debt.

The factors that brought a credit culture to the United States are at work in other nations, too.

Germany: West Germans doubled their consumer and mortgage debt ratios (debt as a percentage of disposable income) in the decade 1975-85. Household debts now come to 62 percent of disposable income.

Japan: Until recently, banks weren’t allowed to offer consumer installment loans. But credit has been available from other sources. Even though interest rates were often more than 50 percent, consumer debt ratios doubled between 1975 and 1985. Consumer debt load is now larger in Japan than in Britain.

United Kingdom: Household debts rose rapidly in the ’80s after credit was deregulated. Interest rates on consumer loans are often more than 25 percent. The home mortgage debt ratio is now larger than it is in the United States. Household debts rose rapidly in the ’80s after credit was deregulated. Interest rates on consumer loans are often more than 25 percent. The home mortgage debt ratio is now larger than it is in the United States.

Converging ratios: In 1970, the Japanese household debt ratio was only 29 percent of the American ratio; today it is 72 percent of the American. Similarly, West Germans have gone from 32 to 83 percent of the American ratio, and Britons from 64 to 85 percent. In 1970, the Japanese household debt ratio was only 29 percent of the American ratio; today it is 72 percent of the American. Similarly, West Germans have gone from 32 to 83 percent of the American ratio, and Britons from 64 to 85 percent.

“Over the past two decades, there has been a striking convergence among the household debt ratios. Since 1983, however, debt growth in the United States has accelerated above that in Japan and Germany, bringing the prior trend toward convergence to at least a temporary halt” (Dorothy B. Christelow, “Converging Household Debt Ratios of Four Industrial Countries,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Quarterly Review, Winter 1987-88).

Not only are Americans borrowing more, they have been, until recently, saving less, which is “cause for concern.” The article warns that America’s trade deficit is due in part to “a sharp decline in the U.S. personal savings rate accompanied by a surge in consumer borrowing” to pay for imported goods.

Consumer Debt in Latin America

The use of credit in Latin American nations varies widely. Large segments of society use cash only; most people do not have bank accounts or buy many consumer goods. In some nations credit is widely used. Overindebtedness may, in fact, be a bigger problem than it is in the U.S.

Merchants often offer installment credit for appliances and other large purchases. Buyers must prove creditworthiness, and a large down payment may be required. Money in the bank is usually required to cover the credit limit. To establish creditworthiness it also helps to own land. Interest on credit purchases might be double the inflation rate. If inflation is unpredictable, full payment will have to come within a shorter period.

Credit cards are more difficult to obtain than in the U.S. or Western Europe and are a sign of wealthier status. Most credit cards cannot be used outside the nation of origin; an international card may be obtained through a special application.

Consumer Debt in Canada

The average Canadian adult owes more than $4,500 in consumer installment debts. Ten years ago, the consumer debt load was 15 percent of income after taxes. Now it is 20 percent, as it is in the United States.

Ten years ago, Canadians saved about 12 percent of their income after taxes. Now Canadians save only 9 percent. Incomes have risen 126 percent in the past decade. But since costs have risen similarly, families cannot buy any more than they used to.

Inflation has disguised some changes. Savings have almost doubled in dollar amounts, but the value of those savings has fallen 25 percent. Canadians, like many others around the world, are poorly prepared for an unexpected job or personal crisis, or another recession.

10 Warning Signals

Here are 10 warning signals that can help you determine whether you are headed for financial trouble. If any apply to you, it’s time to take a closer look at your budget. If three or four apply, you are in difficulty.

- Using credit to buy things you used to be able to buy with cash.

- Getting new loans or extensions to pay your debts.

- Paying only the minimum amount due on charge accounts.

- Receiving overdue notices from creditors.

- Using savings to pay bills that you used to pay from checking.

- Borrowing on life insurance with little chance of repayment.

- Depending on overtime pay to make ends meet each month.

- Using your checking account “overdraft” to pay regular bills.

- Juggling rent or mortgage money to pay other debts.

- Using credit card cash advances to pay living expenses.

If you are in financial difficulty, you may wish to contact a professional counseling service. Local governments or banks may offer help or direct you to an organization that charges little or nothing for such help. Possible sources of help:

- In Australia, various welfare and church agencies such as Lifeline.

- In Canada, ask the Credit Counseling Service of Metropolitan Toronto for a service near you.

- In New Zealand and the United Kingdom, the Citizens Advice Bureau.

- In the United States, the Consumer Credit Counseling Service.

Author: Michael Morrison